When Speech Isn’t Free: Young Thug and Gunna’s Racketeering Case Puts Lyrics on Trial

Legal experts and local hip-hop advocates weigh in on the past, present and future implications of using music as evidence.

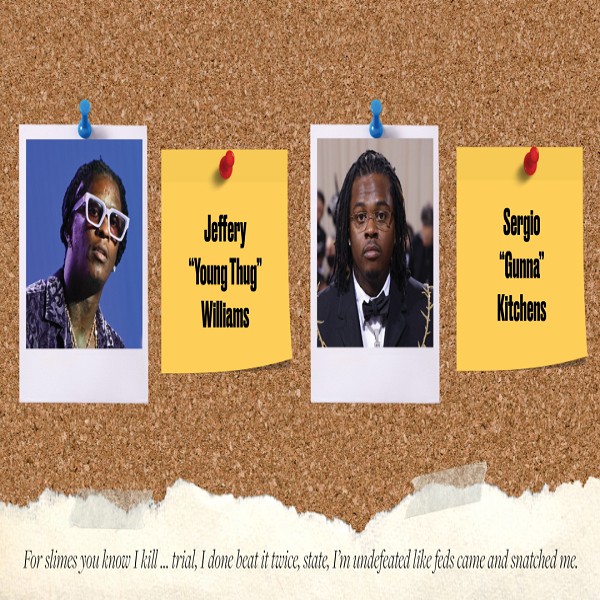

Prosecutors are using the lyrics to Young Thug’s songs, such as these lines from “Take It To Trial,” in the Atlanta rapper’s racketeering case. (Illustration by Nayion Perkins/Capital B. Photo of Young Thug by Paras Griffin/Getty Images; photo of Gunna by Taylor Hill/Getty Images)

One of the few areas of the city relatively untouched by gentrification in recent years is Cleveland Avenue, a well-worn street in southeast Atlanta bustling with activity and homegrown culture where longtime residents gather to celebrate Cleveland Avenue Day.

Lately, however, it’s more famously known as the area that shaped and informed much of rapper Young Thug’s music. The same music that propelled him from neighborhood stardom to the national spotlight with platinum-selling records is now being used as evidence of alleged criminal activity.

On May 9, a sweeping 88-page, 56-count indictment filed in Fulton County named Young Thug (Jeffery Lamar Williams) and fellow Atlanta rapper Gunna (Sergio Kitchens), along with over two dozen others, as alleged conspirators in an organized crime organization that started in the Cleveland Avenue area. The indictment accuses Young Thug as being a co-founder of the gang Young Slime Life, and alleges members of YSL committed multiple murders, shootings, and carjackings spanning a decade. Young Thug and Gunna (who is signed to Thug’s Young Stoner Life Records, an imprint he launched in 2016), were charged with conspiracy to violate the state’s Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act, and the indictment quotes lyrics from music videos as evidence, including tracks like Young Thug’s “Anybody” and “Eww.”

“To weaponize these words by charging overt acts to support a supposed conspiracy is unconscionable and unconstitutional,” Young Thug’s lawyer, Brian Steel, wrote in an emergency motion filed with the Georgia Superior Court on May 13. Gunna’s lawyers also argued that using his lyrics as evidence of wrongdoing could lead to criminal charges against “any artist with a song referencing violence.”

While Young Thug and Gunna’s cases are still unfolding [Gunna was denied bond on May 23 and has a trial date set for January 2023, while Young Thug’s bond proceedings were delayed], the use of their rap lyrics in the indictment drops the case into long-standing national debate over the practice. Prosecutors, like Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis, believe their lyrics are evidence of their alleged crimes.

“I believe in the First Amendment. It is one of our most precious rights,” Willis said in a May press conference. “However, the First Amendment does not protect people from prosecutors using it as evidence if it is such. In this case, we put it as ‘overt, predicate act’ in the RICO count, because we believe that’s exactly what it is.”

But opponents — among them criminal justice reform advocates, hip-hop scholars, and free speech advocates — say rap lyrics should be protected by free speech.

Young Thug and Gunna aren’t the first rap defendants to have lyrics used against them.

The use of rap lyrics as evidence in criminal proceedings has been a normal occurrence since the early 1990s. Mac “The Camouflage Assassin” Phipps, Boosie Badazz, Mac Dre, Mayhem Mal — the list of rappers who’ve had their lyrics brought into court as evidence is long. Erik Nielson, a professor of liberal arts at the University of Richmond who specializes in the relationship between Black creative expression and U.S. law, and Andrea L. Dennis, associate dean for faculty development and John Byrd Martin chair of law at the University of Georgia School of Law, are authors of the 2019 book Rap on Trial: Race, Lyrics, and Guilt in America, which examines inequities in the criminal legal system and the failures of First Amendment protections. They point to nearly 500 instances where rap music or lyrics were used in the course of a criminal case. And the trend seems to show no signs of ending, especially with more artists using social media and releasing music independently without traditional gatekeepers.

One recent case that further opened the door for rap lyrics to be used as evidence came in January 2021 when a Maryland Court of Appeals ruled rap lyrics can be used as evidence of a defendant’s guilt in court, a verdict that came as part of Lawrence Montague’s 2017 murder conviction. Montague rapped the lyrics in question to a friend over a jail phone in 2017, while he was awaiting trial for murder and gun-related charges.

“I’m gucci. It’s a rap. Fuck can they do for — about a rap?” he asked when his friend warned him about the lyrics.

The state ended up using the rap to convict him weeks later, and he was sentenced to 50 years. Montague appealed the admission of the lyrics, but the courts denied the appeal in January 2021, setting a “very dangerous precedent,” Montague’s trial lawyer, Tyler Mann, told Complex. Mann believes the lyrics were the sole piece of evidence used to convict Montague.

Recently, there’s been heavy pushback from big-name artists who oppose the practice. In January, Jay-Z’s lawyer drafted a letter to New York state lawmakers signed by artists including Robin Thicke, Meek Mill, and Killer Mike that pushed for the passage of Senate Bill S7527, or “Rap Music on Trial,” which would limit the ability of prosecutors to use song lyrics as evidence in court. In May, the bill was passed by the New York state Senate, a promising step in setting a new precedent, though it still won’t completely outright ban the use of lyrics in court. Instead, it would require prosecutors to show to a jury that what they’re presenting is “literal, rather than figurative or fictional.” The bill is now set to move to the New York General Assembly for a vote before it can be signed into law.

In a 2016 interview with Genius, Nielson explained that rap lyrics are typically used in one of three ways: They’re treated as confessions if they’re written after the crime; they’re treated as proof of intent if they’re written before the crime; or they’re classified as “threats,” meaning the lyrics are the crime themselves.

In Young Thug’s case, his lyrics are being used as evidence of criminal activity. 2018’s “Just How It Is” includes the lyrics “Gave the lawyer close to two mil, he handles all the killings,” while 2021’s “Take It To Trial” has “For slimes you know I kill … trial, I done beat it twice, state, I’m undefeated like feds came and snatched me.” In all, lyrics from nine of his songs, ranging from 2014 to 2021, were listed in the indictment, which were described as “an overt act in furtherance of the conspiracy.”

A disproportionate effect on rappers

While many activists, academics, and legal experts have made the case that this practice is unfair, it is legal? In 2013, with the case Dawson v. Delaware, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled it unconstitutional to use protected speech as evidence when that speech is irrelevant to the case. But this has not worked to protect rap lyrics.

Though Dawson v. Delaware set a “heightened evidentiary standard” as it pertains to art protected by free speech, in many cases rap lyrics have not met that standard. And so they continue to be allowed in court cases.

As Georgia State University College of Law professor Tanya Washington explained, courts should take into account the ways that violent imagery and expletives in rap lyrics could prejudice a jury against the defendant who wrote them. “The admission of [rap lyrics] invites fact finders to make racialized judgements about Black defendants that deprive them of the full panoply of constitutional rights,” she said.

In a 2020 article about the 2015 murder conviction of Knoxville, Tennessee, rapper Christoper Bassett, whose lyrics were used as evidence against him, Emerson Sykes and Leila Rafei with the American Civil Liberties Union wrote, “If song lyrics could be used as evidence in criminal trials, many of the most famous artists in history would be in serious trouble.”

But not all song lyrics are created equal.

Song lyrics from other genres that a defendant wrote or listened to have been used to convict before. Washington noted the 2002 murder case of Justin Barber, who was sentenced to life in prison for killing his wife. The fact that Barber downloaded Guns N’ Roses’ song “Used to Love Her” before the murder occurred was used in the trial. But, she said, the use of rap music is, “racialized in a way that other genres are not.”

And research suggests people do react differently to violent rap lyrics than similar content in other genres.

One experiment cited in an Indiana University study, Bad Rap for Rap: Bias In Reactions to Music Lyrics, showed “when a violent lyrical passage is represented as a rap song, or associated with a Black singer, subjects find the lyrics objectionable, worry about the consequences of such lyrics, and support “some form of government regulation.” That same lyrical passage, when presented as being written by a country or folk singer, created “less critical,” reactions.

Thomas Harvey, executive director of the Children’s Defense Fund and former justice project director at the Advancement Project National Office, said that there’s a “metanarrative” of Black male violence that underpins the use of violent rap lyrics as evidence.

“Within that metanarrative, violent rap lyrics can never be anything other than autobiographical,” he said. “Rappers aren’t artists participating in a fiction to make money, they are only criminals who are confessing their criminality.”

Manny Faces, founder of the Atlanta-based Center for Hip-Hop Advocacy, an organization which aims to broaden public perception on hip-hop music and culture, said the perception in court that rap lyrics are autobiographical while violent lyrics in other kinds of music are perceived as art shows how little anyone outside of hip-hop culture understands the genre.

“At best, this double-standard represents a callous cultural insensitivity that has no place in the courtroom,” he said. “At worst, it is evidence of ongoing, race-driven bias in our legal system.”

And that’s one of the biggest criticisms about lyrics being used in court — it’s a practice that disproportionately affects rap artists.

“The fact that it’s directly related to hip-hop and rap music being used in courts and it’s not the other genres being used in court, you already know what it is, you don’t even have to guess on that one,” says DeJuan Cross, Atlanta-based producer/engineer and music supervisor for The Hip-Hop Caucus, an organization whose mission is to use cultural expression to empower communities impacted by injustice. “If you ever listen to country music, there’s so much violence, there’s so much going on in those songs, it’s like, come on. But that’s a problem that we have in America and the world, period — racism and white supremacy.”

In the Young Thug case, it’s unclear what role the lyrics will ultimately play at his trial, and lyrics and social media posts are not the only evidence presented in the indictment. But one thing is certain: The fundamental fight over whether violent lyrics might have anything to do with the innocence or guilt of the rapper who wrote them keeps raging.